There are moments in history when faith is tested not by argument, but by fire.

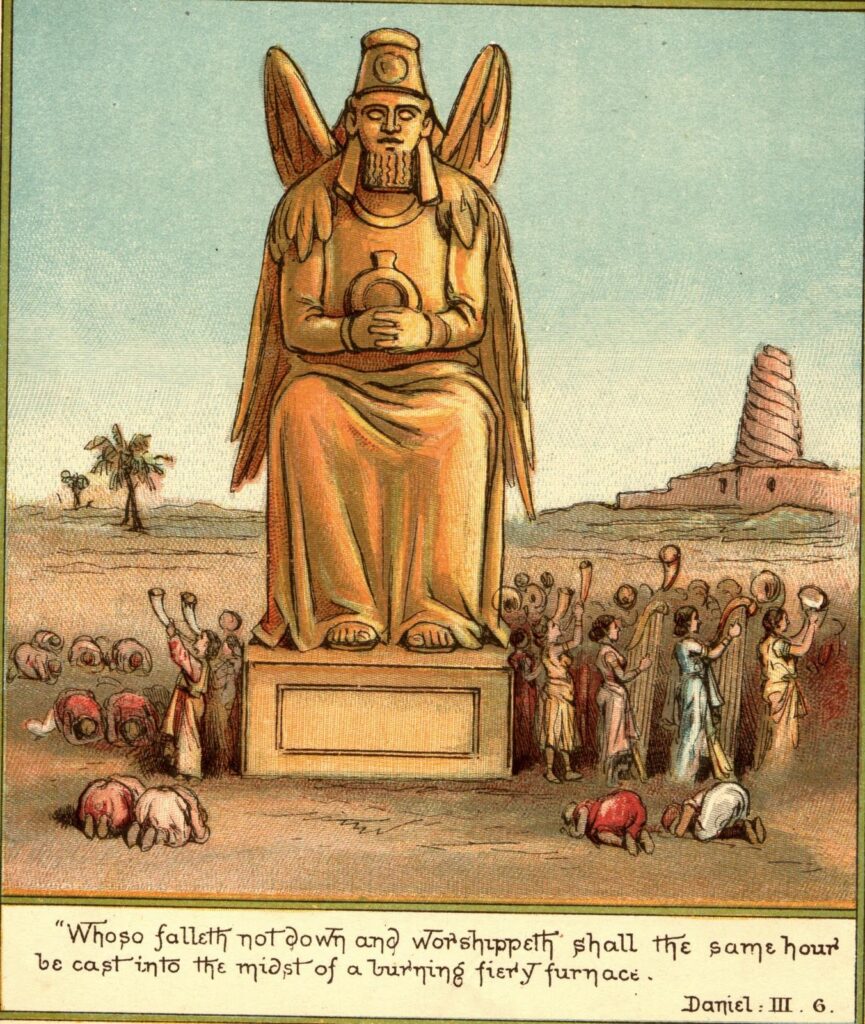

When King Nebuchadnezzar raised his towering golden image and demanded universal worship, three young men—Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah—stood in holy defiance. Exiles in Babylon, stripped of their homeland, their temple, and even their Hebrew names, they were renamed Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego. But while Babylon could rename them, it could not remake them. They still belonged to the God of Israel.

The Making of Abednego

Abednego—originally Azariah, meaning “Yahweh has helped”—was of noble lineage from Judah, chosen for his intellect and character to serve in the court of Babylon after the siege of Jerusalem. The chief official of Nebuchadnezzar gave him the name Abednego, meaning “servant of Nebo” or possibly “servant of the shining fire.” It was an attempt to erase his covenant identity and assimilate him into Babylonian religion and culture.

Yet even as a captive, Azariah remained free. Along with his companions, he endured a three-year program designed to train them in the ways of the empire. Their brilliance and integrity earned them high administrative posts in Babylon—but their faith placed them in direct conflict with its idolatry.

The Scapegoats of Empire

When the king decreed that all must bow before his golden statue, the crowd obeyed—except for these three young men. Their refusal was not political rebellion; it was spiritual fidelity. They declared:

“We will not bow, even if our God does not deliver us.”

That moment of faith made them targets. In the eyes of Babylon, they were enemies of order—scapegoats for the empire’s insecurity. As philosopher René Girard would later describe, the scapegoat mechanism is how societies preserve their illusion of peace: by uniting against an innocent victim. Babylon’s fury was no different. To preserve its false unity, it cast the faithful into the flames.

The Worship Furnace

The furnace was heated seven times hotter than usual—a symbolic perfection of wrath. The soldiers who carried them to the flames perished instantly, yet the three fell into the inferno alive. Inside that fire, something greater than fear arose: worship.

This sacred moment is preserved in the Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Holy Children, an ancient passage found after Daniel 3:23 in the Greek Septuagint. Accepted as Scripture in some Christian traditions and as apocryphal in others, this song gives voice to the faith that refused to burn.

The passage unfolds in three movements:

1️⃣ The Penitential Prayer – Azariah confesses the sins of his people and acknowledges God’s justice:

“We have sinned and acted wickedly… Yet with a contrite heart and humble spirit may we be received.”

Even as an innocent sufferer, he takes upon himself the guilt of his people—a gesture that prefigures the redemptive suffering of the Messiah.

2️⃣ The Vision in the Fire – Nebuchadnezzar peers into the flames and cries out:

“Did we not cast three men bound into the fire? But I see four men loose, walking in the midst of the fire… and the fourth looks like a son of the gods.”

That phrase—“like a son of the gods”—stands as one of Scripture’s great prophetic mysteries. Spoken by a pagan king, it captures the limited vocabulary of a man glimpsing the infinite. To Nebuchadnezzar, it was a divine being. To the faithful, it was a revelation: the pre-incarnate Christ, Yeshua, walking in the flames.

This was no angelic messenger—it was the Son of God Himself, appearing before Bethlehem, standing beside His servants in their suffering. In this furnace, the scapegoats of empire are joined by the ultimate Scapegoat—the Lamb of God who will take away the sin of the world.

3️⃣ The Song of Praise – Realizing they are untouched by the flames, the three raise their voices in worship:

“Praise and exalt Him above all forever!”

The refrain resounds through all creation—sun, moon, stars, mountains, seas, and living things—each called to glorify the One who reigns over fire itself.

The Revelation in the Fire

When the king called them out, not even the smell of smoke clung to them. Nebuchadnezzar—once proud and defiant—was moved to praise their God. The scapegoats had become witnesses; the fire meant for their destruction became the setting of their vindication.

They were promoted to higher office, their faith honored before the empire that tried to erase them. But beyond their promotion, their story illuminated a deeper spiritual truth:

The furnace is where God reveals Himself.

From Babylon to Calvary

Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego foreshadowed the innocent sufferer, the righteous one condemned for the peace of others. Their ordeal mirrors the scapegoat mechanism that reached its fulfillment at the Cross, where Yeshua—the true Scapegoat—was accused, condemned, and sacrificed to reconcile a world at war with itself.

They were delivered through the fire.

He entered into the fire of human sin.

They stood with God.

He became the offering that brought God to man.

The worship furnace thus becomes both a symbol of divine companionship in suffering and a prophecy of ultimate redemption. It shows that the God who stood with His servants in the fire is the same God who would step into the furnace of our world to bear its heat Himself.

The Enduring Lesson

Even in exile, even without a temple, prophet, or priest, these young men prayed:

“We follow You with our whole heart, we fear You and seek Your face. Do not put us to shame.”

The flames still test faith today. The world still seeks its scapegoats. Yet the same Presence still walks among the fire.

The furnace still burns.

The Scapegoat still saves.

And the Son still walks among the flames.